There are two ideas I want to explore in this blog:

1) That the concept of decentralisation, applied to English language teaching, can

- bring power down to the level of the learner

- build on the success of previous teaching and learning approaches, and improve on their shortcomings

- provide answers to teacher and learner problems

2) That learning a language is more effective when the learner builds their own decentralised system for learning.

I’m going to be exploring these two ideas in my roles as a teacher of English and as a learner of German and Bosnian/Serbian/Croatian. So, feel free to join me on this journey!

Introduction

As an English Teacher I’ve noticed that language teaching is often ineffective – learners get frustrated with learning languages, and annoyed at the way that languages are taught. I include myself here as a learner. So much language learning is essentially boring and lifeless!

Therefore, I started to think about what have been my BEST lessons, where the learners were really tuned in, having fun and I didn’t feel like an authority figure pushing the learners through endless exercises.

Here are a few examples:

1) Making Beer

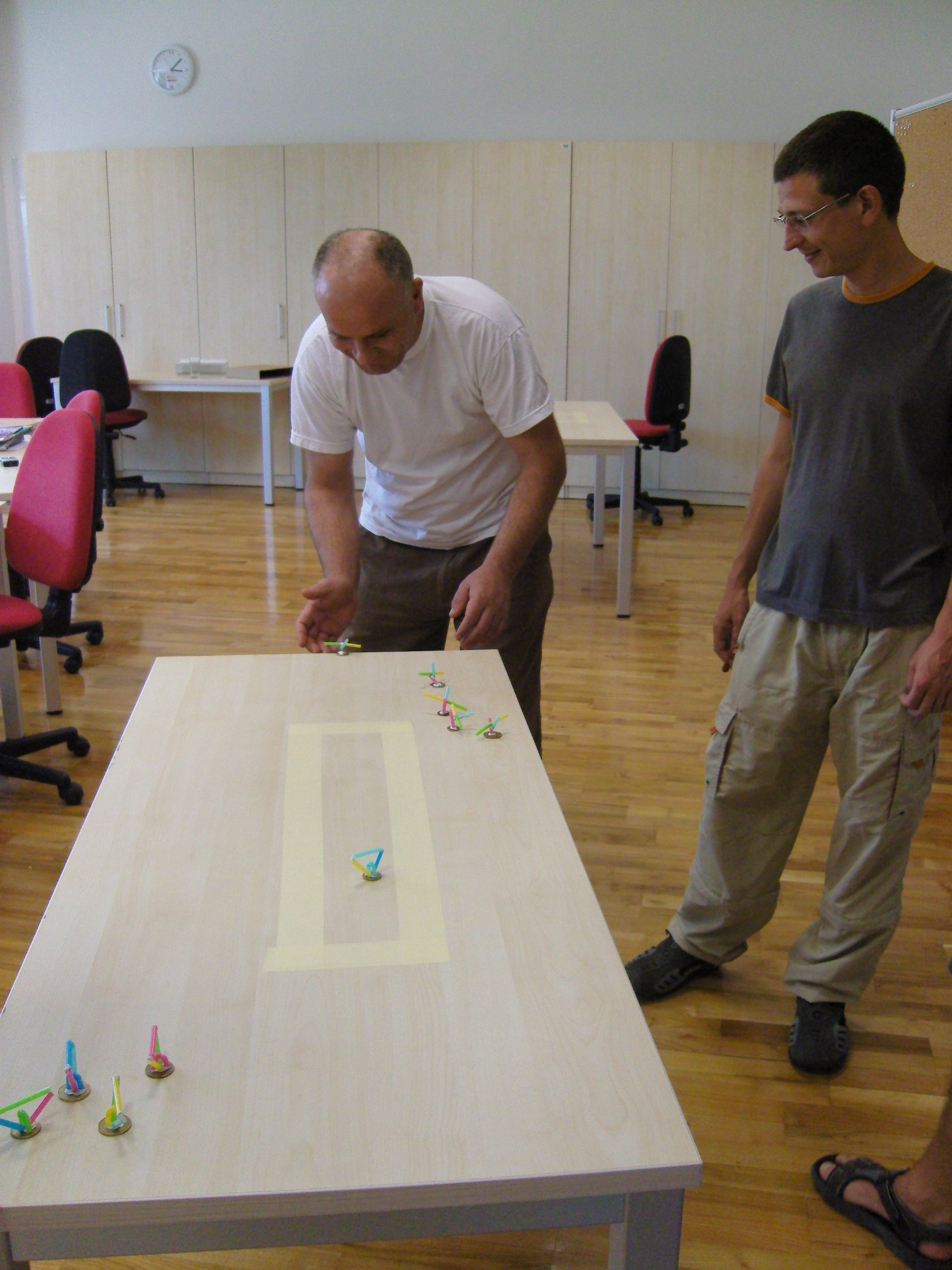

2) Games

3) Team Building Activities

What these activities all have in common is that they are social, fun and Teaching/ Learning is to a large degree, Decentralised.

Teaching Methods, Currents, Trends and Tendencies

There are three currents in ELT that have influenced me as a teacher:

– Task Based Teaching

– Teaching Unplugged/ Dogme

– Learner Autonomy

Task Based teaching focusses attention on real life tasks and concentrates on meaning over form. It works extremely well, but the crucial element is task design. I have done some great Task Based lessons but I don’t have the time (or institutional support) to devote to planning a whole series of lessons like this – the workload is too much!

Teaching Unplugged/ Dogme, with its core principles of being conversation-driven, materials-light and with a focus on emergent language is a much-needed antidote to the pre-dominance of ‘imported’ materials, but it is difficult to institutionalise this approach the way the EFL industry is structured as of now (see Jason Renshaw’s post here) and it can be a real jolt to learner’s expectations: “What – there’s no textbook?”

Moreover, while the principles of Teaching Unplugged are clear, the process of implementation is not – how do you operationalise the principles behind Dogme in the face of learner-, institution- and industry-level expectations?

Learner Autonomy works well in some settings, often teaching situations with a high degree of institutional backing, but in my opinion it is too radical to be adopted in the typical ELT settings I have experienced (language academies, summer schools).

Another reason why the above currents are not more prevalent could be to do with the lack of profit they generate!

Principles and future direction

So, using this blog I want to explore the idea of more durable, sustainable change in my own teaching and learning, which perhaps has implications for the wider EFL community.

My exploration will be based around three principles:

-

There is no central authority in a decentralised classroom

-

Language problems should be solved at the lowest level capable of solving them, starting with the individual student

-

There should be co-responsibility for learning

However, I’m not callling for a ban, or stopping the use of coursebooks (this debate has become sterile). Instead, I am looking to create a balance between Centralisation and Decentralisation, between Efficiency and Learning.

My last word on Methods and Approaches, Trends and Tendencies in ELT is this – no matter what the approach, good learners learn with, or in spite of, bad teachers. So what is it about these learners that makes them effective?

How does this work in practice? Don’t some learners, especially at a lower level, need some kind of structure and an authority figure?

Language learners are conditioned by the educational culture they went through. Expectations are shaped by their learning experiences and environment – which often involved a textbook, drilling, gap-fill exercises, rote learning and little reflection. During my school experiences of learning Spanish this was certainly the case!

This means that the teacher is expected to play a dominant role and learners are, to a large degree, dependent on the teacher. If you had this kind of schooling you might expect a well-ordered classroom, with clearly proscribed activities and little interaction. I’m still surprised at how often some of my students ask me for a ‘grammar’ lesson! Of course, this is a broad generalisation but one I’ve often found to be true, this being exactly what communicative teaching was meant to overcome.

In practice, I do think that learners deserve some kind of structure – I like to know where I’m going when I learn a language and you can just look unprofessional turning up and asking ‘what do you want to do?’. But there needs to be some negotiation – depending on the level and motivation of the learners.

I therefore think that the following elements are key:

Building consensus – However you choose to teach, then building consensus on what you are going to teach is important. If you are going to use a coursebook, then use it – but obviously not all of it is relevant. Creating a negotiated or process syllabus (see Clarke 1991) is a deep-end choice for teachers with a lot of institutional support, but a more workable solution is to give learners a ‘menu’ and get them to choose what is most important for them. At the least, if using a coursebook, get the learners to read the syllabus and identity what they DON’T need.

Goal-setting – Getting learners to set specific learning goals provides motivation for learning. Memorising a poem, having a conversation about music and ordering a pizza are all achievable language learning goals. Improving my grammar is not – it’s too general and difficult to measure. Additionally, as a teacher set goals for your own performance as well, e.g. with this group I’m going to improve my boardwork, or over the next few months I’ll bring more pronunciation teaching into my lessons.

Planning – Try and make medium-term plans for a group or course (e.g. 10/12 week), and build in check points, or milestones, at regular intervals. Planning in this way also enables you to do all your photocopying in one go! I do think there’s an argument that planning and course design should be included even in inititial teacher education, on CELTA courses. Otherwise, you’re often just limping along to the sound of the coursebook syllabus with very little control or agency.

Review – At the end of a course, or group of lessons, review the plan with your learners. What worked well? What did they like? Would they change anything if they had to do the course again?

The implementation of Decentralised Teaching is something I’ll be speaking about in future posts, which will include specific classroom activities.

CONCLUSION

I will be exploring Decentralising Teaching and Learning over the next year and I’m looking forward to your feedback.

Let’s start!

FAQs

Isn’t Decentralised Teaching and Learning just another fad? I’ve based this blog on my experience in 7 countries over 8 years, where I’ve seen learners struggle with how they are expected to learn. I’ve also seen teachers stifled by the demands of the profession and the real-world expectations of language schools and sometimes, of learners. Also, I don’t believe that one method is enough to alleviate this situation as different methods all have a lot to offer. I believe that the system we’ve created is ineffective – therefore the problem needs to solved at a system level!

Are you against coursebooks? Yes and No. When I was a rookie teacher, it took me quite a few years to get to grips with English grammar – as I wasn’t taught it at school (which makes you wonder why we teach it so much in class). So coursebooks really helped me to ‘find my feet’ as a teacher. But over time, as coursebooks have become all-singing, all-dancing books-with-bells-on I sometimes feel that I’m just in the classroom to push out product and that I’m becoming de-skilled! Also, having met coursebook writers, they are just as passionate about the good and bad aspects of ELT and language learning.

What is Decentralised teaching? You haven’t provided much academic backing for your claims. Decentralised Teaching is about making certain things more important and other things less important. The learner (the learners motivation, drive, life experience, capabilities and potential) and learning relationships (with peers, tandem partners, penpals) should (surely) be at the centre of the process, and the materials more to the periphery. On the second point, yes, there is little academic backing to my claims as yet! I’m a busy working teacher and it takes a long time to write good posts! Plus, the literature on Decentralisation is spread across dozens of disciplines, from social science to organisational theory. But I’m working on a more thorough conceptualisation.

How can you have no authority in the classroom – there has to be some authority? What I’m saying is that they doesn’t need to be a central authority in the classroom – that the teacher can take more of a backseat sometimes! I’m all for dictionaries in class, using authoritative sources, but when teaching adults – I think there should be more autonomy for learners and co-responsibility for learning.

Why the song “Stuck in the Middle with You’? This describes the way I’ve often felt in the classroom as a teacher – stuck in the middle, the victim of a long list of expectations: from the learners, the institution, the ‘industry’, down to my own. I’m the authority figure, imparting language to learners ‘chalk-and-talk’ style. This doesn’t seem to be the most productive way of learning languages in the 21st century.

Hi Paul,

First of all, it’s great to know that your post is still alive! Your topic of your blog (Decentralised Teaching) comes to confirm what I was already thinking about ever since we graduated from Trinity Dip.

At the moment, I am working as a Teacher Trainer and Head of a Mentoring and Coaching Programme. What I have been trying to let my trainees realise is that coursebooks can be useful to a certain extent but we should try to cut our umbilical cords at a certain stage of professional maturity. Living in a coursebook-oriented culture where administrators, teachers and learners frown up with the idea of trying other non-traditional methods can make my work a bit challenging. Just like you said in the FAQs, I am neither for or against the idea. I do think that there is room for other approaches as long as our main aim is achieved,

On the other hand, I do not want them (my trainees) to get the wrong idea; however, it is really imperative that we are able to help our learners meet their expectations by providing different alternatives.

George.

Hi George,

Great to hear from you – glad that you are doing well. Thanks for you insightful comments too, I really like your phrase “we should try to cut our umbilical cords at a certain stage of professional maturity” – that’s brilliant.

Paul

Hi Paul

Congrats on the new blog!

I agree with your point about authority devolving to learners. In an adult class especially there is no reason why the learners shouldn’t decide what happens in a major way. As a teacher I would find it very liberating to be part of a lesson planned by the students rather than me. Of course I think the learners have the right to delegate responsibility for planning the event to their teacher if they choose, but this is too often the default setting and other options are not explored.